Ceva's theorem

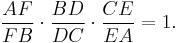

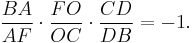

Ceva's theorem is a theorem about triangles in Euclidean plane geometry. Given a triangle ABC, let the lines AO, BO and CO be drawn from the vertices to a common point O to meet opposite sides at D, E and F respectively. Then

This equation uses signed lengths of segments, in other words the length AB is taken to be positive or negative according to whether A is to the left or right of B in some fixed orientation of the line. For example, AF/FB is defined as having positive value when F is between A and B and negative otherwise.

The converse is also true: If points D, E and F are chosen on BC, AC and AB respectively so that

then AD, BE and CF are concurrent. The converse is often included as part of the theorem.

The theorem is often attributed to Giovanni Ceva, who published it in his 1678 work De lineis rectis. But it was proven much earlier by Yusuf Al-Mu'taman ibn Hűd, an eleventh-century king of Zaragoza.[1]

Associated with the figures are several terms derived from Ceva's name: cevian (the lines AD, BE, CF are the cevians of O), cevian triangle (the triangle DEF is the cevian triangle of O); cevian nest, anticevian triangle, Ceva conjugate. (Ceva is pronounced Chay'va; cevian is pronounced chev'ian.)

The theorem is very similar to Menelaus' theorem in that their equations differ only in sign.

Contents |

Proof of the theorem

A standard proof is as follows:[2]

First, the sign of the left-hand side is positive since either all three of the ratios are positive, the case where O is inside the triangle (upper diagram), or one is positive and the other two are negative, the case O is outside the triangle (lower diagram shows one case).

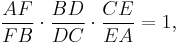

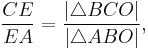

To check the magnitude, note that the area of a triangle of a given height is proportional to its base. So

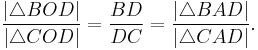

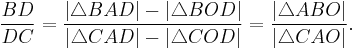

Therefore,

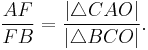

(Replace the minus with a plus if A and O are on opposite sides of BC.) Similarly,

and

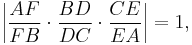

Multiplying these three equations gives

as required.

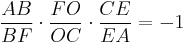

The theorem can also be proven easily using Manelaus' theorem.[3] From the transversal BOE of triangle ACF,

and from the From the transversal AOD of triangle BCF,

The theorem follows by dividing these two equations.

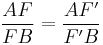

The converse follows as a corollary.[4] Let D, E and F be given on the lines BC, AC and AB so that the equation holds. Let AD and BE meet at O and let F′ be the point where FO crosses AB. Then by the theorem, the equation also holds for D, E and F′. Comparing the two,

But at most one point can cut a segment in a given ratio so F=F′.

Generalizations

The theorem can be generalized to higher dimensional simplexes using barycentric coordinates. Define a cevian of an n-simplex as a ray from each vertex to a point on the opposite (n-1)-face (facet). Then the cevians are concurrent if and only if a mass distribution can be assigned to the vertices such that each cevian intersects the opposite facet at its center of mass. Moreover, the intersection point of the cevians is the center of mass of the simplex. (Landy. See Wernicke for an earlier result.)

Routh's theorem gives the area of the triangle formed by three cevians in the case that they are not concurrent. Ceva's theorem can be obtained from it by setting the area equal to zero and solving.

The analogue of the theorem for general polygons in the plane has been known since the early nineteenth century (Grünbaum & Shephard 1995, p. 266). The theorem has also been generalized to triangles on other surfaces of constant curvature (Masal'tsev 1994).

See also

- Projective geometry

- Median (geometry) - an application

References

- Russell, John Wellesley (1905). "Ch. 1 §7 Ceva's Theorem". Pure Geometry. Clarendon Press. http://books.google.com/books?id=r3ILAAAAYAAJ.

- Grünbaum, Branko; Shephard, G. C. (1995). "Ceva, Menelaus and the Area Principle". Mathematics Magazine 68 (4): 254–268. doi:10.2307/2690569. JSTOR 2690569.

- Hogendijk, J. B. (1995). "Al-Mutaman ibn Hűd, 11the century king of Saragossa and brilliant mathematician". Historia Mathematica 22: 1–18. doi:10.1006/hmat.1995.1001.

- Landy, Steven (December 1988). "A Generalization of Ceva's Theorem to Higher Dimensions". The American Mathematical Monthly 95 (10): 936–939. doi:10.2307/2322390.

- Masal'tsev, L. A. (1994). "Incidence theorems in spaces of constant curvature". Journal of Mathematical Sciences 72 (4): 3201–3206. doi:10.1007/BF01249519.

- Wernicke, Paul (November 1927). "The Theorems of Ceva and Menelaus and Their Extension". The American Mathematical Monthly 34 (9): 468–472. doi:10.2307/2300222.

External links

- Menelaus and Ceva at MathPages

- Derivations and applications of Ceva's Theorem at cut-the-knot

- Trigonometric Form of Ceva's Theorem at cut-the-knot

- Glossary of Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers includes definitions of cevian triangle, cevian nest, anticevian triangle, Ceva conjugate, and cevapoint

- Conics Associated with a Cevian Nest, by Clark Kimberling

- Ceva's Theorem by Jay Warendorff, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Ceva's Theorem" from MathWorld.